- World

- Oct 14

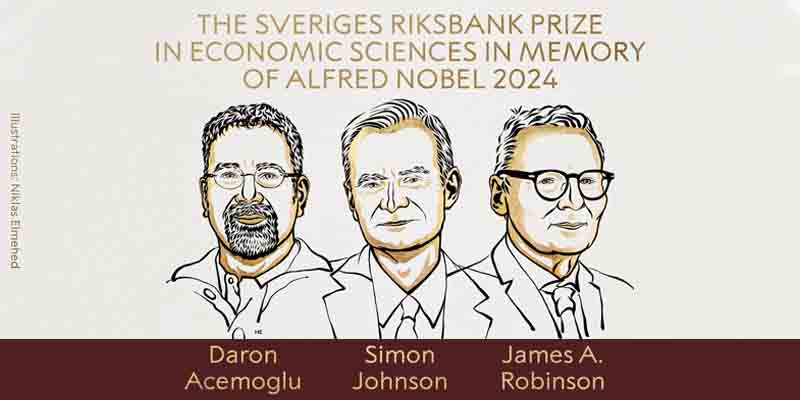

3 US-based academics win Nobel for Economics

• Three US-based academics won the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences for their work on how institutions are formed and affect prosperity.

• Simon Johnson and James Robinson, both British-American, and Turkish-American Daron Acemoglu were commended for their research into why global inequality persists, especially in countries dogged by corruption and dictatorship.

• The Prize, formally known as the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, is the last of this year’s crop of Nobel Prizes.

About the Prize

Unlike the other Nobel Prizes, the economics award wasn’t established in the will of Alfred Nobel. In 1968, Sveriges Riksbank (Sweden’s central bank) established the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel. The prize is based on a donation received by the Nobel Foundation in 1968 from Sveriges Riksbank on the occasion of the bank’s 300th anniversary. The prize amount is the same as for the Nobel Prizes and is paid by the Riksbank. The first prize in economic sciences was awarded to Ragnar Frisch and Jan Tinbergen in 1969.

The prize in economic sciences is awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, Stockholm, Sweden, according to the same principles as for the Nobel Prizes that have been awarded since 1901.

Colonial institutions

The laureates have contributed innovative research about what affects countries’ economic prosperity in the long run. Their insights regarding how institutions influence prosperity show that work to support democracy and inclusive institutions is an important way forward in the promotion of economic development.

By examining the various political and economic systems introduced by European colonisers, Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson have been able to demonstrate a relationship between institutions and prosperity. They have also developed theoretical tools that can explain why differences in institutions persist and how institutions can change.

The richest 20 per cent of the world’s countries are now around 30 times richer than the poorest 20 per cent. Moreover, the income gap between the richest and poorest countries is persistent; although the poorest countries have become richer, they are not catching up with the most prosperous. This year’s laureates have found new and convincing evidence for one explanation for this persistent gap – differences in a society’s institutions.

Rich countries differ from poor ones in many ways – not just in their institutions – so there could be other reasons for both their prosperity and their types of institutions.

Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson examined Europeans’ colonisation of large parts of the globe. One important explanation for the current differences in prosperity is the political and economic systems that the colonisers introduced, or chose to retain, from the sixteenth century onwards.

The laureates demonstrated that this led to a reversal of fortune. The places that were, relatively speaking, the richest at their time of colonisation are now among the poorest. In addition, they used mortality figures for the colonisers, among other things, and found a relationship – the higher mortality among the colonisers, the lower today’s GDP per capita.

When Europeans colonised large parts of the globe, the institutions in those societies changed. This was sometimes dramatic, but did not occur in the same way everywhere. In some places the aim was to exploit the indigenous population and extract resources for the colonisers’ benefit. In others, the colonisers formed inclusive political and economic systems for the long-term benefit of European migrants.

The laureates have shown that one explanation for differences in countries’ prosperity is the societal institutions that were introduced during colonisation. Inclusive institutions were often introduced in countries that were poor when they were colonised, over time resulting in a generally prosperous population. This is an important reason for why former colonies that were once rich are now poor, and vice versa.

Some countries become trapped in a situation with extractive institutions and low economic growth. The introduction of inclusive institutions would create long-term benefits for everyone, but extractive institutions provide short-term gains for the people in power. As long as the political system guarantees they will remain in control, no one will trust their promises of future economic reforms. According to the laureates, this is why no improvement occurs.

However, this inability to make credible promises of positive change can also explain why democratisation sometimes occurs. When there is a threat of revolution, the people in power face a dilemma. They would prefer to remain in power and try to placate the masses by promising economic reforms, but the population are unlikely to believe that they will not return to the old system as soon as the situation settles down. In the end, the only option may be to transfer power and establish democracy.

Manorama Yearbook app is now available on Google Play Store and iOS App Store