- India

- Feb 09

- Shashidhar K.J.

The urgent need for data protection law in India

Following outrage and calls for users to abandon WhatsApp, Facebook has delayed the rollout of the controversial privacy policy for the messaging service to May 15, 2021. While it might seem that the change in the privacy policy came out of the blue, it should not come as a surprise. It’s important to understand why these changes in the privacy policy came and the contours of it.

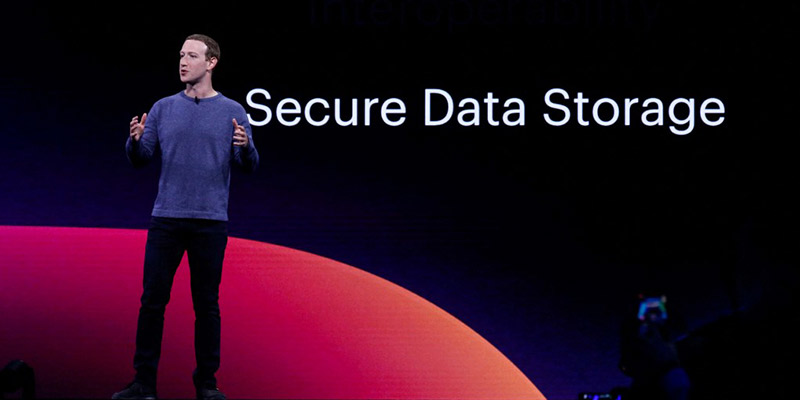

For a little over five years, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg has been elaborating on quarterly investor calls on how the company will start leveraging its group companies Instagram and WhatsApp. Facebook has hit peak advertisement load for users, that means it cannot insert more advertisements into user’s feeds without breaking user experience. It meant that the company’s online advertising growth engine showed signs of plateauing.

Facebook now wants to grow the advertising business and marketplace capabilities of Instagram and use the payments feature of WhatsApp to gather granular data financial data of its users and use it as a flywheel for Facebook’s advertising business.

Reading WhatsApp’s new privacy policy with a fine comb shows that its assurances to the user’s privacy ring hollow and that it is an attempt to legitimize its ambitions for growing the Facebook Group’s business.

India is a key testing ground for Facebook’s ambitions and WhatsApp’s access to the Unified Payments Interact (UPI) is an essential cog to gather more user’s financial data.

The messaging flywheel

WhatsApp has clarified that all messages exchanged by users are end-to-end encrypted, that it doesn’t keep logs of people messaging and calling users, location shared by users are not visible to Facebook, and that the contacts book is not visible to Facebook. These claims are partly true.

While messages and media exchanged are end-to-end encrypted and that location data shared is not visible to Facebook, the claim that it does not keep a log of messages and calls does not hold. As part of its efforts to curb misinformation and disinformation, WhatsApp has introduced new features where it displays whether a message is forwarded or forwarded many times. This is possible by reading the metadata of the message sent which includes time stamps.

The WhatsApp privacy policy also mentions that it stores forwarded media temporarily in encrypted form on our servers to aid in more efficient delivery of additional forwards as part of its retention policy.

But the most egregious ingress into user’s privacy comes when it comes to the sections that deal with the WhatsApp for Business and Payments section. WhatsApp for Business is a product that Facebook developed where it allowed businesses of different sizes to set up storefronts and interface with customers directly through the application for a fee. The policy warns users that “some businesses might be working with third-party service providers (which may include Facebook) to help manage their communications with their customers. For example, a business may give such third-party service provider access to its communications to send, store, read, manage, or otherwise process them for the business.”

Also, news websites have a ‘share on WhatsApp button’. When users click on this button, Facebook receives the information aiding in building a user’s profile.

Facebook now discloses a metric called “Family daily active people” defined as a registered and logged-in user of one or more of Facebook's products who visited at least one of these products through a mobile device application or web browser on a given day. The idea here being that posts, messages, payments, and data exchanged on Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp are interoperable through this “family profile”.

What this means is that transactions with WhatsApp for Business Accounts are fair game for collection by the company to enrich their advertising service’s capabilities, whether they are on Facebook or not.

For example, a rising advertising format on the Facebook app has been the click-to-message ad where users can start messaging a business directly on Messenger or WhatsApp when they see an advertisement. The idea here is that Facebook wants to close the loop on advertising the product and facilitate the transaction for the product.

“So click-to-messaging ads, which the ads run in Facebook and Instagram but then link you to WhatsApp or Messenger, is a product that’s growing well. As you can complete more payments in WhatsApp and Messenger, you would expect it to be worth more for businesses to bid more there, which is why we’re so far focused on making it so that the payments can be free or really as cheap as possible. Because we think that from a business perspective, we will get some of the value just by having the services be more valuable for businesses and the ad prices that they’ll bid in the auction,” Zuckerberg said in January 2020.

Whose law are we following anyway?

Essentially, what Facebook bifurcated user data into three groups for WhatsApp. First, where personal messages and data exchanged between users are end-to-end encrypted where Facebook can claim that it does respect user’s privacy (to an extent as its efforts to curb misinformation prove otherwise).

Second data set it collects is from WhatsApp from Business accounts which have transaction and purchase information from merchants.

Third, Facebook also accesses user financial data even when they initiate a person-to-person (P2P) transaction on a personal chat.

WhatsApp has a separate privacy policy for the UPI where it mentions that it collects users’ financial information from the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) and Payments Service Provider Banks (PSP) regarding both sender and receiver bank accounts.

Financial data of Indian users collected may be shared with the parent Facebook Group and the NPCI, which owns and governs the UPI ecosystem, makes provisions for the same.

Google has similar arrangements with the NPCI for its payment service Google Pay where the company is permitted to access users’ financial information to better their advertising services.

Concerns raised in the aftermath of the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal in 2018 seem to have been side-stepped. The fear was that users’ financial information would be misused and in response the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) issued a circular in April 2018 which mandated that all payments data should be localised in India and that companies had six months to comply without clear operating guidelines for the same.

The RBI and the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeITY) denied a full service roll out of the payments service for WhatsApp till November 2020. The RBI finally elaborated what information it wanted to be localised and WhatsApp said that it has complied with the orders for the RBI and was given the final go-ahead to launch their services.

But data localization does not necessarily prevent abuse of data by external parties. Remember Cambridge Analytica, an external party, obtained personal information of millions of users from Facebook to carry out targeted political advertisements on users to influence the outcomes of the Brexit vote and the 2016 US general elections.

Facebook’s contrition for its role in the Cambridge Analytica scandal seemed short lived. It seems to have forgotten the role it played in the turbulent exit of the UK from the European Union and the chaotic reign of Donald Trump as president of the United States.

In recent calls with analysts, Facebook is hawking and boasting its increased targeted advertising capabilities now armed with access to users’ financial data.

“Our goal here is to give every individual, entrepreneur and small business access to the same kinds of tools that historically only the big companies have had access to,” Mark Zuckerberg said about building new targeted ad systems in the January 2021 analyst call. “So, when you hear people argue that we shouldn’t be doing these things or that we should go back to the old days of untargeted television ads, I think that what they’re really arguing for is a regression where only the largest companies have this capacity, small businesses are severely disadvantaged and competition is diminished..... So, we’re building tools to let businesses store and manage their WhatsApp chats using our secure hosting infrastructure, if they would like. And we’re in the process of updating WhatsApp’s privacy policy in terms of service to reflect these optional experiences,” he added.

It is unclear on who will be able access these targeted ad systems at scale and what controls are there to prevent abuse. It’s important to remember that these arrangements between the NPCI and technology companies are made in a regulatory gray space in India since the Personal Data Protection (PDP) Bill is still being debated in the Indian Parliament.

Moreover, the United States does not have a federal data protection law and there isn’t any serious discussion on data collected by US technology companies from other countries and how their actions impact those countries.

The PDP bill states that financial data constitutes sensitive personal data which requires very explicit consent from users when companies try to access it. But the arguments made by the RBI on the PDP Bill do not inspire confidence to protect users. The RBI said that financial data should not be classified as sensitive personal data and that only biometric and health data, and information on sexual orientation, religious beliefs, union membership and political opinion should be classified as sensitive personal data.

When WhatsApp asked users to comply with the changes to the privacy policy, it left users without agency or much choice. The only choice users had to stop Facebook to collect data was to leave the platform, a tall order considering its near ubiquitous use in the country. The rules and arrangements made by the NPCI and technology companies to protect users’ data do not carry explicit legal backing or real consequences for the companies for failing to uphold them, simply because there is no Personal Data Protection law in force.

The government of India writing to WhatsApp to withdraw the changes to the privacy policy carries little meaning when it removed the blocks preventing Facebook from accessing the UPI system and not paying attention to Mark Zuckerberg’s intentions stated consistently and publicly for five years.

Facebook has had to devise separate rules for the European Union (EU) and Ireland where the rules of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) on accessing and using private data are more stringent. Users in the EU and Ireland do not have to share their WhatsApp data with Facebook to improve their advertising practices and products, Niamh Sweeny, director for policy for WhatsApp confirmed in a series of tweets. The GDPR places the onus on companies to behave more responsibly with users data and mandates that service providers can collect only essential information which is absolutely necessary to provide services. The cost of non-compliance or breach is steep for companies operating in the EU and they may be fined €20 million or 4 per cent of the company’s annual global turnover.

In contrast, the Information Technology Act in India, which deals with rules governing data, currently places the onus on the users to prove harm was done do them in their complaint to the adjudicating authority and award proportional compensation.

The government is looking to expand the scope of the PDP Bill and include non-personal data. Consultations and discussions are underway and media reports mention that it could be tabled in the Budget session of the Parliament. However, there are key aspects to keep in mind. Non-personal data also includes mixed data sets which have elements of personal data as well. Bifurcating and regulating both will be a challenge and more thought needs to go into how non-personal data can be regulated. But the need of the hour is protection of personal data.

There is an urgent need to pass a comprehensive data protection law as soon as possible, which places the interests of the users first in India. The urgency is necessitated as the majority of users of technology companies like Google, Facebook and Amazon, etc are in India. These companies paint a rosy picture of India where they can experiment with new technologies and business models with Indian users exposing them to risks while shielding their most profitable users in the United States. The dynamic must change for the benefit of all Indian users.

(Shashidhar K.J. is associate fellow at Observer Research Foundation, Mumbai. The views expressed here are personal.)