- World

- Dec 08

- Jabin T. Jacob

China’s challenge to global democracy

2018 marks 40 years since China launched its economic reforms, and opening up that changed its domestic economic structure as well as set it on course to being the global economic giant it is today. Now, China’s significance in the global economy is not in question whether as an industrial producer, as a consumer of raw materials, or as a pioneer in pushing the frontiers of technology and its applications.

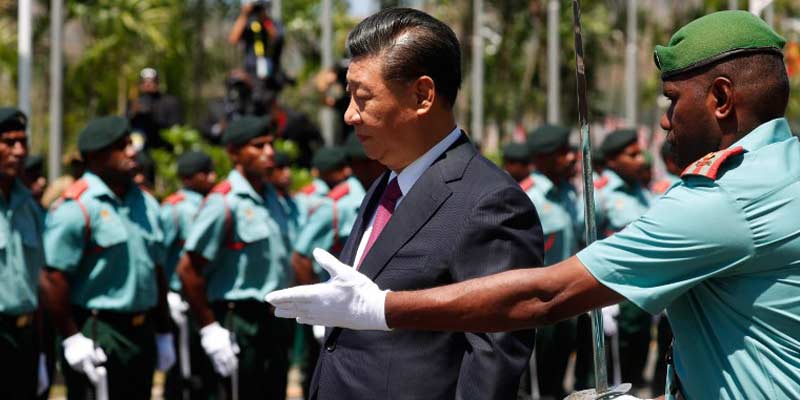

What has also been apparent since at least 2012 when Xi Jinping took over as general secretary of the Communist Party of China (CPC), if not earlier, is that China’s economic power is being put to political uses at both the regional and global levels. Somehow, the west, led by the US, appears not to have anticipated that the ‘rise of China’ would bring with it a challenge to not just western economic domination but also to American military might and perhaps, most importantly, to the very idea of democracy and other largely western political values and ideals.

A dynamic foreign policy

It is easy for observers to see China’s aggressive actions in the South China Sea, occupying and reclaiming features in contravention of international law, for example for what it is - a straightforward territorial grab. But the world is still largely unsure of how to deal with such Chinese projects as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the slow ingress of Chinese political influence in western and other open societies using the very democratic openness that Beijing denies to its own citizens at home.

Also known as the ‘One Belt, One Road’, the BRI is ostensibly a series of infrastructure development projects connecting China overland through Central Asia to Europe and by sea through Southeast Asia all the way to West Asia and Africa. In both instances, South Asia plays a central role with the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) being one of the key projects.

India has objected to the BRI for a number of reasons ranging from a lack of transparency in Chinese terms and conditions to the fact that the CPEC runs through Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK). Indeed, India’s reasons have been justified by news of countries such as Sri Lanka falling into a debt trap to the Chinese and consequently having to lease out for 99 years strategic assets like their Hambantota port.

And yet, there is something of a too-big-to-fail element to the BRI - there might be individual projects that might fail and individual countries that might receive the short end of the straw, but by and large Eurasia’s and Africa’s need for physical infrastructure is real and China seems to be the only country that appears to have both the means and the willingness to invest in these countries.

India lacks the means even though it might be willing and is bedeviled by a poor implementation record despite some tall promises it has made to several countries over the decades. It might also be asked what exactly New Delhi has done all these decades to ensure that PoK remained an issue both on the national and international radar.

The Chinese have, by contrast, constantly and consistently reiterated their claims to the de facto independent island of Taiwan and of late, to the South China Sea, working to shrink the former’s international space and in the latter case, to divide opposition to China’s actions within the ASEAN grouping, where some countries are also claimants.

The political challenge

However, it is in the realm of the political that the greatest challenge from China lies.

In his report to the 19th CPC National Congress held in October 2017, Xi declared that his country respected the right of the people of all countries to choose their own development path and that it stood “for democracy in international relations and the equality of all countries”. These are fine-sounding words except that Xi also follows up by saying he believed in “contributing Chinese wisdom and strength to global governance”. In other words, he offers a ‘Chinese model’ for the rest of the world to emulate as the preferred ‘development path’. In this path, however - if one understands the nature of the CPC and the latest internal developments in China - democracy has no place; survival of single-party rule by the CPC takes priority over all else.

China is attempting to promote its model of politics and economic development through the BRI and the steady undermining of international law and accepted norms of state-to-state behaviour as in the South China Sea. Even in the case of India, the Doklam standoff in mid-2017 showcased the Chinese capacity for selective interpretation of international treaties, the willingness to make temporary or false promises for achieving its objectives and the ability to make use of the ongoing truce to return to bad behaviour by fortifying its presence in occupied Bhutanese territory. As a result, India is unable to fulfil in their entirety, its treaty obligations to Bhutan.

The ‘China model’ is also evident in the reports of Chinese bribing Sri Lankan politicians and its indifference to the nature of regimes in power in its neighbourhood as long as they are willing to support Chinese interests against India or the west.

China has scant respect for a democratic world order or its institutions. Its approach has always been to be part of major global institutions to ensure that its voice and interests were not ignored but also to start new ones where it would dominate and set the agenda. Cases in point include the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank - which in many ways stands against the Japan-supported Asian Development Bank - and the Lancang-Mekong Cooperative Mechanism, which undermines the much older ASEAN-centric Greater Mekong Sub-region project and the Mekong River Commission.

Technology to aid authoritarianism

Finally, a big part of the Chinese political model is the uses that China puts cutting-edge technology to. Consider China’s policing of the Internet and banning of foreign online search engines such as Google, social media such as Facebook or Twitter and messaging platforms like WhatsApp. Then there is China’s launch of a facial recognition software across the country that is like a permanent eye on each of its citizens as well as foreigners in the country.

Another recent innovation is the ‘social credit’ system that deducts points for apparent bad behaviour by its citizens. In effect, anti-Party behaviour is immediately punished and can result in everything from lower speeds for your Internet connections to loss of access to public services, including bus and air travel or to public housing.

China’s focus on big data applications and artificial intelligence are all geared towards supporting and creating a new, more durable form of political authoritarianism. In all this, China is both innovator and role model for other current and potential authoritarians.

The rise of China, including the free flow of its capital and its massive propaganda efforts, undermines democracies the world over. This is so because no country has done what China has done in the past 40 years - provide the basic requirements of socioeconomic development and a reasonable standard of living to the vast majority of its citizens and on the scale that it has. This China has done, however, without simultaneously protecting and promoting the democratic and civil rights of its citizens.

For democracies to compete with the Chinese model, they will have to ensure both economic and social well-being and political accountability.

As the only other country with the scale and the potential of China as well as a democratic political system, can India create a sustainable model that ensures both prosperity and democratic rights to all its citizens and thus also an alternative model to China? This might well be the defining question of the 21st century.

Jabin T. Jacob is a China analyst at the National Maritime Foundation in New Delhi. The views expressed here are personal.