- World

- Jul 14

Achieving Zero Hunger by 2030 unlikely

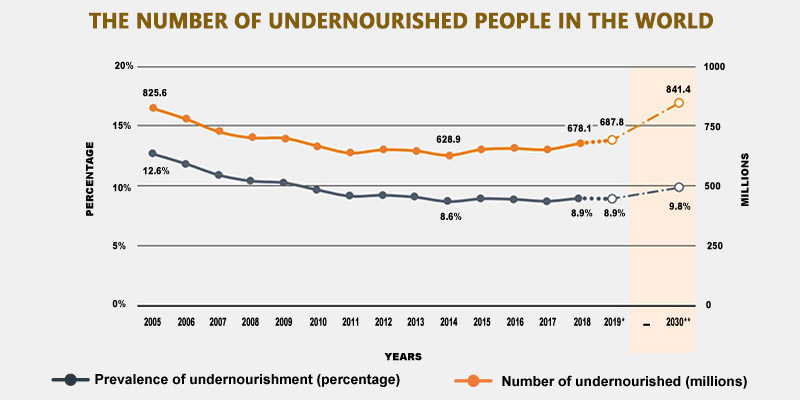

With ten years to go until 2030, the world is off track to achieve the SDG targets for hunger and malnutrition. After decades of long decline, the number of people suffering from hunger has been slowly increasing since 2014.

The trends shown by the prevalence of undernourishment and the prevalence of severe food insecurity based both point to failed progress.

Beyond hunger, a growing number of people have been forced to compromise on the quality and/or quantity of the food they consume, as reflected in the increase in moderate or severe food insecurity since 2014.

Projections for 2030, even without considering the potential impact of COVID-19, serve as a warning that the current level of effort is not enough to reach Zero Hunger ten years from now.

The setback throws into further doubt the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 2 (Zero Hunger).

What are SDGs?

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were adopted by all UN member states in 2015 as a universal call of action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity by 2030.

It consists of 17 goals and 169 targets (UNDP 2016). The SDGs are an ambitious commitment by world leaders, which set out a universal and an unprecedented agenda that embraces economic, environmental and social aspects of the well-being of societies.

New report forecasts grim future

The United Nations says the ranks of the world’s hungry grew by 10 million last year and warns that the coronavirus pandemic could push as many as 130 million more people into chronic hunger this year.

The grim assessment was contained in the latest edition of the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World.

The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World is the most authoritative global study tracking progress towards ending hunger and malnutrition. It is produced jointly by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the International Fund for Agriculture (IFAD), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the UN World Food Programme (WFP) and the World Health Organization (WHO).

The UN agencies estimated that nearly 690 million people, or nearly 9 per cent of the world’s population, went hungry last year, an increase of 10 million since 2018 and of nearly 60 million since 2014.

Asia remains home to the greatest number of undernourished (381 million). Africa is second (250 million), followed by Latin America and the Caribbean (48 million). The global prevalence of undernourishment – or overall percentage of hungry people – has changed little at 8.9 percent, but the absolute numbers have been rising since 2014. This means that over the last five years, hunger has grown in step with the global population.

How pandemic worsened the situation?

As progress in fighting hunger stalls, the COVID-19 pandemic is intensifying the vulnerabilities and inadequacies of global food systems – understood as all the activities and processes affecting the production, distribution and consumption of food.

While it is too soon to assess the full impact of the lockdowns and other containment measures, the report estimates that at a minimum, another 83 million people, and possibly as many as 132 million, may go hungry in 2020 as a result of the economic recession triggered by COVID-19

Food insecurity and malnutrition

The number of people affected by severe food insecurity, which is another measure that approximates hunger, shows a similar upward trend. In 2019, close to 750 million – or nearly one in ten people in the world – were exposed to severe levels of food insecurity.

As for nutrition, progress is being made on decreasing child stunting and low birthweight and increasing exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life.

Worldwide, the prevalence of child stunting in 2019 was 21.3 percent, or 144 million children.

However, prevalence of wasting is notably above the targets and the prevalence of both child overweight and adult obesity is increasing in almost all regions, a worrisome trend that will add to the global burden of disease and increase public health service and health care costs.

Child wasting: The share of children under the age of five who are wasted (that is, who have low weight for their height, reflecting acute undernutrition).

Globally, 6.9 percent of children under five (47 million) were affected by wasting in 2019 – a figure significantly above the 2025 target (5 per cent) and the 2030 target (3 per cent) for this indicator.

A key reason why millions of people around the world suffer from hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition is because they cannot afford the cost of healthy diets.

Costly and unaffordable healthy diets are associated with increasing food insecurity and all forms of malnutrition, including stunting, wasting, overweight and obesity.

The way forward

These trends in hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition must be reversed. COVID-19 is expected to exacerbate these trends, rendering vulnerable people even more vulnerable. Urgent action is needed in order to meet the 2030 targets, even as the world braces for the impact of the pandemic.

Increasing availability of and access to nutritious foods that make up healthy diets must be a key component of stronger efforts to achieve the 2030 targets.

The availability of dietary energy per person has increased globally over the past two decades. However, this has not translated into an increase in the availability of nutritious foods that contribute to healthy diets.

The study calls on governments to:

* Mainstream nutrition in their approaches to agriculture.

* Work to cut cost-escalating factors in the production, storage, transport, distribution and marketing of food, including reducing inefficiencies, and food loss and waste.

* Support local small-scale producers to grow and sell more nutritious foods, and secure their access to markets.

* Prioritise children’s nutrition as the category in greatest need.

* Foster behaviour change through education and communication.

* Embed nutrition in national social protection systems and investment strategies.

Manorama Yearbook app is now available on Google Play Store and iOS App Store