- World

- Oct 12

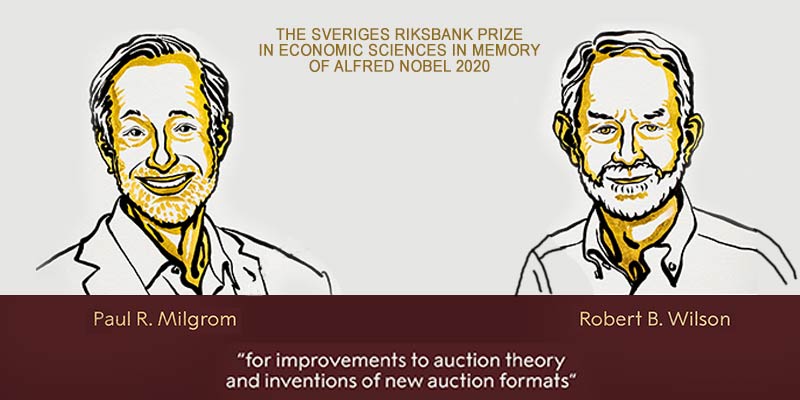

2 Stanford economists win Nobel Prize for work on auction theory

Two American economists won the Nobel Prize for improving the theory of how auctions work and inventing new and better auction formats that are now woven into many parts of the economy.

The discoveries of Paul R. Milgrom and Robert B. Wilson have benefitted sellers, buyers and taxpayers around the world, the Nobel Committee said, noting that the auction formats developed by the winners have been used to sell radio frequencies, fishing quotas and airport landing slots.

Both economists are based at Stanford University in California.

Technically known as the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, the award was established in 1969 and is now widely considered one of the Nobel prizes.

How auctions affect all of us at every level?

People have always sold things to the highest bidder, or bought them from whoever makes the cheapest offer.

Auctions have a long history. In Ancient Rome, lenders used auctions to sell the assets they had confiscated from borrowers who were unable to pay their debts. The world’s oldest auction house, Stockholms Auktionsverk, was founded in 1674 – also for the purpose of selling appropriated property.

Nowadays, when we hear the word auction, we perhaps think of traditional farm auctions or high-end art auctions – but it could just as well be about selling something on the Internet or buying property via an estate agent.

Auction outcomes are also very important for us as taxpayers and as citizens. Our mobile phone coverage depends on which radio frequencies the telecom operators have acquired through spectrum auctions. All countries now take loans by selling government bonds in auctions. So, auctions affect all of us at every level. Moreover, they are becoming increasingly common and increasingly complicated.

This is where this year’s laureates have made major contributions. They have not just clarified how auctions work and why bidders behave in a certain way, but used their theoretical discoveries to invent entirely new auction formats for the sale of goods and services. These new auctions have spread widely around the world.

Auction theory

The outcome of an auction (or procurement) depends on three factors. The first is the auction’s rules, or format. Are the bids open or closed? How many times can participants bid in the auction? What price does the winner pay – their own bid or the second-highest bid?

The second factor relates to the auctioned object. Does it have a different value for each bidder, or do they value the object in the same way?

The third factor concerns uncertainty. What information do different bidders have about the object’s value?

Using auction theory, it is possible to explain how these three factors govern the bidders’ strategic behaviour and thus the auction’s outcome. The theory can also show how to design an auction to create as much value as possible. Both tasks are particularly difficult when multiple related objects are auctioned off at the same time.

This year’s laureates in Economic Sciences have made auction theory more applicable in practice through the creation of new, bespoke auction formats.

Types of auctions

Early auction theory compared bidding strategies and outcomes in four auction formats. They are:

• The Dutch or Clock auction, where the price begins at a high level set by the seller and is gradually decreased until some bidder accepts and pays that price.

The Aalsmeer Flower Auction in the Netherlands relies on Dutch auctions to sell around 20 million flowers per day, and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York uses a form of Clock auction when selling bonds to primary dealers so as to raise funds for the US Treasury.

• The English auction, where bids ascend from a starting price (often suggested by the seller) by open outcries, observed by everybody, until no bidder is willing to make a higher bid, at which point the highest bidder wins and pays a price equal to her final bid.

English auctions are probably the most common format in use today, at least for private single object auctions on online platforms such as eBay.

• The First-price (sealed-bid) auction, where the participants submit a single bid not observed by the others (in sealed envelopes), such that the highest bidder wins and pays what he/she bid.

First-price auctions are common vehicles for companies and organisations to procure goods or services, and for governments to award public contracts or allocate mining leases.

• The Second-price (sealed-bid) or Vickrey auction, where bidders submit bids in sealed envelopes, and the highest bidder wins but pays the second-highest bid.

Second-price auctions are less common, but they too have been used for centuries, for example when selling collectibles, and are presently used by internet-search engines when selling advertising space.

These common auction formats are used to sell a wide range of objects, assets, and commodities.

The concept of ‘winner’s curse’

Bidders in auctions with common values run the risk of other participants having better information about the true value. This leads to the well-known phenomenon of low bids in real auctions, which goes by the name of the winner’s curse. Say that you win the auction of a raw diamond. This means that the other bidders value the diamond less than you do, so that you may very well make a loss on the transaction.

How this year’s laureates developed new auction formats?

Robert Wilson developed the theory for auctions of objects with a common value – a value which is uncertain beforehand but, in the end, is the same for everyone. Examples include the future value of radio frequencies or the volume of minerals in a particular area. Wilson showed why rational bidders tend to place bids below their own best estimate of the common value: they are worried about the winner’s curse – that is, about paying too much and losing out.

Paul Milgrom formulated a more general theory of auctions that not only allows common values, but also private values that vary from bidder to bidder. He analysed the bidding strategies in a number of well-known auction formats, demonstrating that a format will give the seller higher expected revenue when bidders learn more about each other’s estimated values during bidding.

Milgrom and Wilson have not only devoted themselves to fundamental auction theory. They have also invented new and better auction formats for complex situations in which existing auction formats cannot be used. Their best-known contribution is the auction they designed the first time the US authorities sold radio frequencies to telecom operators.

The auction was initially done through a process known as a beauty contest, in which companies had to provide arguments for why they, in particular, should receive a licence. This process meant that telecom and media companies spent huge amounts of money on lobbying. The revenue generated by the process was limited, however.

In the 1990s, as the market for mobile telephony expanded, the responsible authority in the US, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), realised that beauty contests were no longer tenable.

Milgrom and Wilson – partly with Preston McAfee – invented an entirely new auction format, the Simultaneous Multiple Round Auction (SMRA). This auction offers all objects (radio frequency bands in different geographic areas) simultaneously. By starting with low prices and allowing repeated bids, the auction reduces the problems caused by uncertainty and the winner’s curse.

When the FCC first used an SMRA in July 1994, it sold 10 licences in 47 bidding rounds for a total of $617 million.

The first spectrum auction using an SMRA was generally regarded as a huge success. Many countries (including Finland, India, Canada, Norway, Poland, Spain, the UK, Sweden, and Germany) adopted the same format for their spectrum auctions. The FCC’s auctions alone, using this format, have brought more than $120 billion over twenty years (1994–2014) and, globally, this mechanism has generated more than $200 billion from spectrum sales. The SMRA format has also been used in other contexts, such as sales of electricity and natural gas.

Subsequently, auction theorists – often working with computer scientists, mathematicians and behavioural scientists – have refined the new auction formats. They have also adapted them to reduce the opportunities for manipulation and cooperation between bidders.

Milgrom is one of the architects of a modified auction (the Combinatorial Clock Auction) in which operators can bid on “packages” of frequencies, rather than individual licences. This type of auction requires significant computational capacity, as the number of possible packages grows very quickly with the number of frequencies for sale.

Milgrom is also a leading developer of a novel format with two rounds (the Incentive Auction). In the first round, you buy radio spectra from current licence-holders. In the second round, you sell these relinquished frequencies to other actors who can manage them more efficiently.

The laureates’ ground-breaking research about auctions has been of great benefit, for buyers, sellers and society as a whole.

Manorama Yearbook app is now available on Google Play Store and iOS App Store