- World

- Oct 16

India ranks 94 in Global Hunger Index

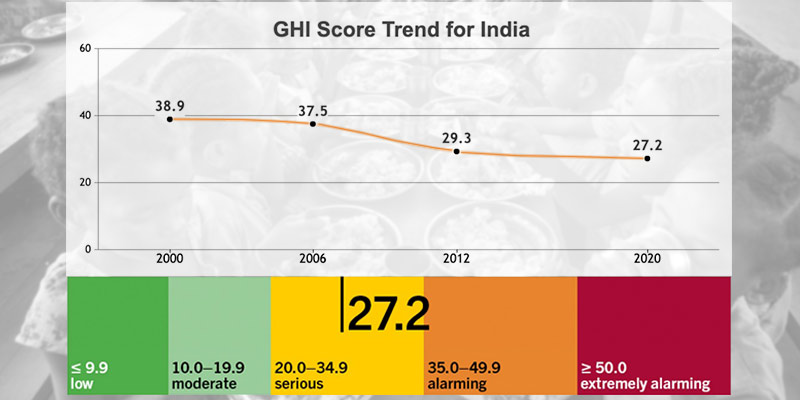

India ranks 94 among 107 countries in the Global Hunger Index 2020. With a score of 27.2, India has a level of hunger that is ‘serious’, according to the report which was published on October 16. India was ranked 102 out of 117 countries in the 2019 index. As per the report, 14 per cent of India’s population is undernourished. The country also recorded a child stunting rate of 37.4 per cent.

Neighbouring Bangladesh, Myanmar and Pakistan too were in the ‘serious’ category but ranked higher than India in this year’s hunger index. While Bangladesh ranked 75, Myanmar and Pakistan were in the 78th and 88th position respectively. Nepal in 73rd and Sri Lanka in 64th position were in the ‘moderate’ hunger category.

As many as 17 countries, including China, Belarus, Ukraine, Turkey, Cuba and Kuwait, shared the top rank with GHI scores of less than five.

What is the Global Hunger Index?

The Global Hunger Index (GHI) is a tool designed to comprehensively measure and track hunger at global, regional, and national levels. It is a peer-reviewed annual report, jointly published by Concern Worldwide and Welthungerhilfe.

GHI scores are calculated each year to assess progress and setbacks in combating hunger. It is designed to raise awareness and understanding of the struggle against hunger, provide a way to compare levels of hunger between countries and regions, and call attention to those areas of the world where hunger levels are highest and where the need for additional efforts to eliminate hunger is greatest.

How are the scores calculated?

GHI scores are calculated using a three-step process that draws on available data from various sources to capture the multidimensional nature of hunger.

First, for each country, values are determined for four indicators:

• Undernourishment: The share of the population that is undernourished (that is, whose caloric intake is insufficient).

• Child Wasting: The share of children under the age of five who are wasted (that is, who have low weight for their height, reflecting acute undernutrition).

• Child Stunting: The share of children under the age of five who are stunted (that is, who have low height for their age, reflecting chronic undernutrition).

• Child Mortality: The mortality rate of children under the age of five (in part, a reflection of the fatal mix of inadequate nutrition and unhealthy environments).

Second, each of the four component indicators is given a standardised score on a 100-point scale based on the highest observed level for the indicator on a global scale in recent decades.

Third, standardised scores are aggregated to calculate the GHI score for each country, with each of the three dimensions (inadequate food supply, child mortality and child undernutrition, which is composed equally of child stunting and child wasting) given equal weight.

This three-step process results in GHI scores on a 100-point GHI Severity Scale, where 0 is the best score (no hunger) and 100 is the worst.

Highlights of Global Hunger Index 2020

• The 2020 Global Hunger Index (GHI) shows that although hunger worldwide has gradually declined since 2000, in many places progress is too slow and hunger remains severe. These areas are highly vulnerable to a worsening of food and nutrition insecurity exacerbated by the health, economic, and environmental crises of 2020.

• Alarming levels of hunger have been identified in 3 countries — Chad, Timor-Leste, and Madagascar — based on GHI scores. Food and nutrition insecurity in Chad are driven by regional conflict, frequent drought, limited income-generating opportunities, and restricted access to social services.

Far too many individuals are suffering from hunger and undernutrition:

* Nearly 690 million people are undernourished.

* 144 million children suffer from stunting, a sign of chronic undernutrition.

* 47 million children suffer from wasting, a sign of acute undernutrition.

* In 2018, 5.3 million children died before their fifth birthdays, in many cases as a result of undernutrition.

• Hunger worldwide, represented by a GHI score of 18.2, is at a ‘moderate’ level, down from a 2000 GHI score of 28.2, classified as ‘serious’.

• In Africa South of the Sahara and South Asia, hunger is classified as ‘serious’, owing partly to large shares of people who are undernourished and high rates of child stunting. Moreover, Africa South of the Sahara has the world’s highest rate of child mortality, while South Asia has the world’s highest rate of child wasting.

• In contrast, hunger levels in Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, East and Southeast Asia, and West Asia and North Africa are characterised as ‘low’ or ‘moderate’, although hunger is high among certain groups within these regions.

• South Asia has the largest number of undernourished people in the world. South Asia’s prevalence of undernourishment as of 2017–2019 was 13.4 percent. While this rate is lower than that for Africa South of the Sahara, South Asia has the highest number of undernourished people in absolute terms, with 255 million people undernourished in the region.

• South Asia’s child wasting rate is the highest of any world region. In 2019 the child wasting rate for South Asia was 14.8 percent, compared with 6.9 percent in Africa South of the Sahara.

• Despite declines in recent years, child mortality in South Asia is still unacceptably high, with improvements in child nutrition needed. India — the region’s most populous country — experienced a decline in under-five mortality in this period, driven largely by decreases in deaths from birth asphyxia or trauma, neonatal infections, pneumonia, and diarrhea. However, child mortality caused by prematurity and low birthweight increased, particularly in poorer states and rural areas.

• Inequalities within country borders are pervasive, and it is crucial to understand which groups face the greatest challenges. For each country, national averages ought not obscure the very real hardships experienced by the most marginalised groups.

• Looking back at trends over the past 10 to 20 years, most countries have experienced improvements. Even in several countries where hunger and undernutrition were considered extremely alarming 20 years ago, the situation has improved dramatically. The near-term future will test the capacity of the world to respond to multiple crises simultaneously — health crises, environmental crises, economic crises, and food security crises among others.

• The world is not on track to achieve the second Sustainable Development Goal — known as Zero Hunger — by 2030. At the current pace, approximately 37 countries will fail even to reach low hunger, as defined by the GHI Severity Scale, by 2030.

• The COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting economic downturn, as well as a massive outbreak of desert locusts in the Horn of Africa, are exacerbating food and nutrition insecurity for millions of people, as these crises come on top of existing hunger caused by conflict and climate extremes.

Manorama Yearbook app is now available on Google Play Store and iOS App Store