- World

- Sep 10

90% countries see decline in Human Development Index score

• India ranked 132 out of 191 countries in the 2021 Human Development Index (HDI), according to a report released by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

• India ranked 131 among 189 countries in the 2020 Human Development Index.

• India’s HDI value of 0.633 places the country in the medium human development category, lower than its value of 0.645 in the 2020 report.

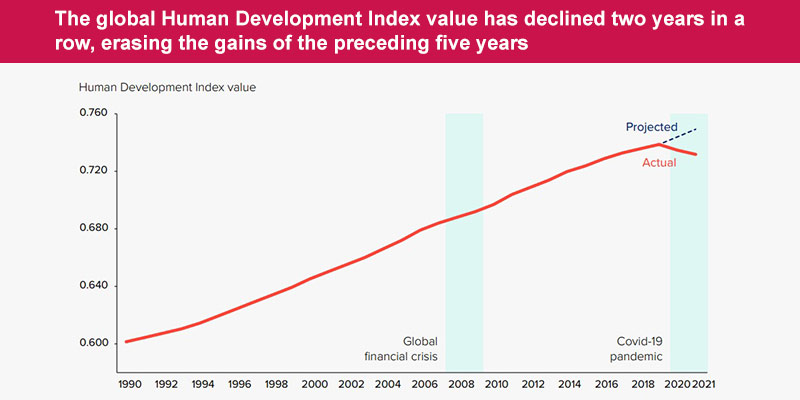

• For the first time on record, the global HDI value declined, taking the world back to the time just after the adoption of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Paris Agreement.

• Every year a few different countries experience dips in their respective HDI values. But a whopping 90 per cent of countries saw their HDI value drop in either 2020 or 2021, far exceeding the number that experienced reversals in the wake of the global financial crisis.

• Last year saw some recovery at the global level, but it was partial and uneven: most very high HDI countries notched improvements, while most of the rest experienced ongoing declines.

• Like global trends, in India’s case, the drop in HDI can be attributed to falling life expectancy — 69.7 to 67.2 years. India’s expected years of schooling stand at 11.9 years, and the mean years of schooling are at 6.7 years, the report said.

Human Development Index (HDI)

• The Human Development Report is published by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) since 1990 as independent and analytically and empirically grounded discussions of major development issues, trends and policies.

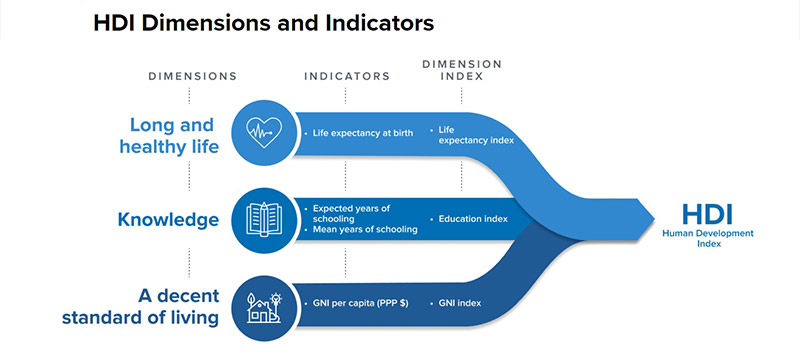

• The Human Development Index (HDI) is a summary measure of average achievement in key dimensions of human development: a long and healthy life, being knowledgeable and have a decent standard of living. The HDI is the geometric mean of normalised indices for each of the three dimensions.

• The HDI was created to emphasize that people and their capabilities should be the ultimate criteria for assessing the development of a country, not economic growth alone.

It is calculated using four indicators:

i) Life expectancy at birth

ii) Mean years of schooling

iii) Expected years of schooling

iv) The Gross National Income (GNI) per capita.

• The HDI uses the logarithm of income, to reflect the diminishing importance of income with increasing GNI. The scores for the three HDI dimension indices are then aggregated into a composite index using geometric mean. Refer to Technical notes for more details.

• The HDI can be used to question national policy choices, asking how two countries with the same level of GNI per capita can end up with different human development outcomes. These contrasts can stimulate debate about government policy priorities.

• The HDI simplifies and captures only part of what human development entails. It does not reflect on inequalities, poverty, human security, empowerment, etc. The Human Development Report Office (HDRO) provides other composite indices as a broader proxy on some of the key issues of human development, inequality, gender disparity and poverty.

• The 2021/22 Human Development Report – which is titled “Uncertain Times, Unsettled Lives: Shaping our Future in a Transforming World” – paints a picture of a global society lurching from crisis to crisis, and which risks heading towards increasing deprivation and injustice.

• The report warns that multiple crises are halting progress on human development, which is going backwards in the overwhelming majority of countries.

• Heading the list of events causing major global disruption are the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which have come on top of sweeping social and economic shifts, dangerous planetary changes, and massive increases in polarisation.

Here are five important things in the report:

1) First back-to-back decline in three decades

For the first time in the 32 years that the UN Development Programme (UNDP) has been calculating it, the Human Development Index, which measures a nation’s health, education, and standard of living, has declined globally for two years in a row.

This signals a deepening crisis for many regions, and Latin America, the Caribbean, Sub-Saharan Africa, and South Asia have been hit particularly hard.

Human development has fallen back to its 2016 levels, reversing much of the progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals which make up the 2030 Agenda, the UN’s blueprint for a fairer future for people and the planet.

The study points to insecurity and polarization of views hampering efforts to bring about the solidarity that is needed to tackle the big global challenges, with data suggesting that those who are most insecure are more likely to hold extremist views. This phenomenon was observed even before the COVID-19 pandemic.

2) COVID-19 is ‘a window into a new reality’

Now into its third year, the pandemic is described in the report as “a window into a new reality”, rather than a detour from business as usual. The development of effective vaccines is hailed as a monumental achievement, credited with saving around 20 million lives, and a demonstration of the huge power of innovation married to political will.

At the same time, the rollout of the vaccines laid bare the huge inequities of the global economy. Access has been paltry in many low-income countries, and women and girls have suffered the most, shouldering more household and caregiving responsibilities, and facing increased violence.

3) We’re living through a new ‘uncertainty complex’

The successive waves of new COVID-19 variants, and warnings that future pandemics are increasingly likely, have helped to compound a generalised atmosphere of uncertainty that was growing in response to the dizzying pace of technological change, its effect on the workplace, and steadily growing fears surrounding the climate crisis.

The study warns that the global upheaval of the pandemic is nothing compared to what the world would experience if a collapse in biodiversity were to occur, and societies found themselves having to solve the challenge of growing food at scale, without insect pollinators.

Three layers of today’s “uncertainty complex” are identified: dangerous planetary change, the transition to new ways of organizing industrial societies, and the intensification of political and social polarisation.

It is not just that typhoons are getting bigger and deadlier through human impact on the environment. It is also as if, through our social choices, their destructive paths are being directed at the most vulnerable among us.

4) There is opportunity in uncertainty

Whilst change is inevitable, the ways in which we react are not. Although there are many well-founded fears surrounding the growing use of Artificial Intelligence, there are many demonstrable upsides to the technology, which is, amongst other things, helping to model the impacts of climate change, improve individualised learning, and help in the development of medicines.

One upshot to the post-COVID world is the creation of novel mRNA vaccine technology, which promises a breakthrough in the way that other diseases are treated. The pandemic has also normalised paid sick leave, voluntary social distancing and self-isolation, all important for our response to future pandemics.

5) We can chart a new course

The last three years could serve to show what we are capable of, when we move beyond conventional ways of doing things, and lead us to transform our institutions so that they are better suited to today’s world.

The analysis contained within the report can help to chart a new course out of the current global uncertainty.

This new direction involves implementing policies that focus on investment, from renewable energy to preparedness for pandemics; insurance, including social protection, to prepare our societies for the ups and downs of an uncertain world; and innovation that helps countries to better respond to whatever challenges come next.

Focus on the three I’s

The report recommends implementing policies that focus on the three I’s — investment, insurance and innovation — will go a long way in helping people navigate the new uncertainty complex and thrive in the face of it.

i) Investment, ranging from renewable energy to preparedness for pandemics and extreme natural hazards, will ease planetary pressures and prepare societies to better cope with global shocks. Consider the advances in seismology, tsunami sciences and disaster risk reduction following the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. Smart, practical investments pay off.

ii) Insurance helps protect everyone from the contingencies of an uncertain world. The global surge in social protection in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic did just that, while underscoring how little social insurance coverage there was before and how much more remains to be done. Investments in universal basic services such as health and education also afford an insurance function.

iii) Innovation in its many forms — technological, economic, cultural — will be vital in responding to unknown and unknowable challenges that humanity will face. While innovation is a whole-of-society affair, government is crucial in this regard: not just in creating the right policy incentives for inclusive innovation but also in being an active partner throughout.

Policies that focus on the three I’s will enable people to thrive in the face of uncertainty. India is already a frontrunner in these areas with its push towards renewable energy, boosting social security for the most vulnerable and driving the world's largest vaccination drive through Co-WIN, supported by UNDP.

Over the last decade, India has lifted a staggering 271 million out of multidimensional poverty.

The country is improving access to clean water, sanitation, and affordable clean energy. India has also boosted access to social protection for vulnerable sections of society, especially during and after the pandemic, with a 9.8 percent increase in the budgetary allocation to the Social Services sector in 2021-22 over 2020-21.

Manorama Yearbook app is now available on Google Play Store and iOS App Store