- World

- Sep 14

50 million people living in modern slavery

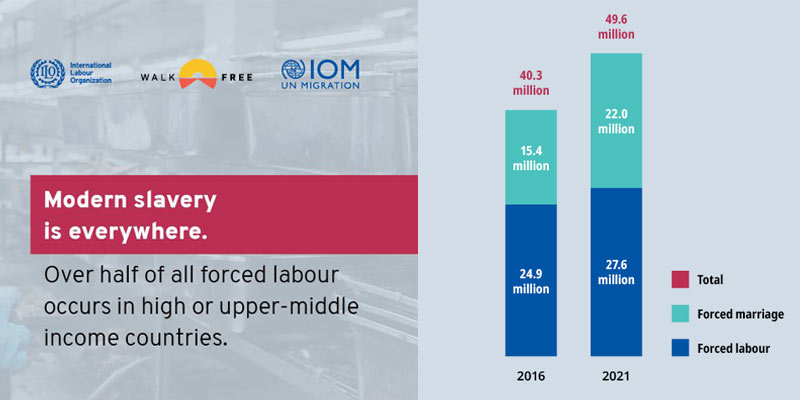

• Fifty million people were living in modern slavery in 2021, according to the latest Global Estimates of Modern Slavery published by the International Labour Organisation (ILO). Of these people, 28 million were in forced labour and 22 million were trapped in forced marriage.

• Both refer to situations of exploitation that a person cannot refuse or cannot leave because of threats, violence, deception, abuse of power or other forms of coercion.

• This number translates to nearly one of every 150 people in the world.

• The number of people in modern slavery has risen significantly in the last five years. As many as 10 million more people were in modern slavery in 2021 compared to 2016 global estimates. Women and children remain disproportionately vulnerable.

• Modern slavery occurs in almost every country in the world, and cuts across ethnic, cultural and religious lines. More than half (52 per cent) of all forced labour and a quarter of all forced marriages can be found in upper-middle income or high-income countries.

Forced labour

• Forced labour, as set out in the ILO Forced Labour Convention, 1930 refers to “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily.”

• Most cases of forced labour (86 per cent) are found in the private sector. Forced labour in sectors other than commercial sexual exploitation accounts for 63 per cent of all forced labour, while forced commercial sexual exploitation represents 23 per cent of all forced labour. Almost four out of five of those in forced commercial sexual exploitation are women or girls.

• State-imposed forced labour accounts for 14 per cent of people in forced labour.

• Almost one in eight of all those in forced labour are children (3.3 million). More than half of these are in commercial sexual exploitation.

• Disruptions to income because of the pandemic led to greater indebtedness among workers and with it reports of a rise in debt bondage among some workers lacking access to formal credit channels. The crisis also resulted in a deterioration of working conditions for many workers, in some cases leading to forced labour.

• No region of the world is spared from forced labour. Asia and the Pacific is host to more than half of the global total (15.1 million), followed by Europe and Central Asia (4.1 million), Africa (3.8 million), the Americas (3.6 million), and the Arab States (0.9 million). But this regional ranking changes considerably when forced labour is expressed as a proportion of the population. By this measure, forced labour is highest in the Arab States (5.3 per thousand people), followed by Europe and Central Asia (4.4 per thousand), the Americas and Asia and the Pacific (both at 3.5 per thousand), and Africa (2.9 per thousand).

• Forced labour is a concern regardless of a country’s wealth. More than half of all forced labour occurs in either upper-middle income or high-income countries. When population is taken into account, forced labour is highest in low income countries (6.3 per thousand people) followed by high income countries (4.4 per thousand).

• Most forced labour occurs in the private economy. Around 86 per cent of forced labour cases are imposed by private actors – 63 per cent in the private economy in sectors other than commercial sexual exploitation and 23 per cent in forced commercial sexual exploitation. State-imposed forced labour accounts for the remaining 14 per cent of people in forced labour.

• Forced labour touches virtually all parts of the private economy. The five sectors accounting for the majority of total adult forced labour (87 per cent) are services (excluding domestic work), manufacturing, construction, agriculture (excluding fishing), and domestic work.

• Migrant workers are more than three times more likely to be in forced labour than non-migrant adult workers.

• Women in forced labour are much more likely than their male counterparts to be in domestic work, while men in forced labour are much more likely to be in the construction sector.

• An estimated 6.3 million people are in situations of forced commercial sexual exploitation at any point in time. Gender is a key determining factor: nearly four out of every five people trapped in these situations are girls or women.

• A total of 3.3 million children are in situations of forced labour, accounting for about 12 per cent of all those in forced labour.

Forced marriage

• Forced marriage is a complex and highly gendered practice. Although men and boys are also forced to marry, it predominantly affects women and girls. Forced marriages occur in every region of the world and cut across ethnic, cultural, and religious lines. The many drivers of forced marriage are closely linked to longstanding patriarchal attitudes and practices and are highly context specific.

• An estimated 22 million people were living in situations of forced marriage on any given day in 2021. This is a 6.6 million increase in the number of people living in a forced marriage between 2016 and 2021, which translates to a rise in prevalence from 2.1 to 2.8 per thousand people.

• Forced marriages take place in every region in the world. Nearly two-thirds of all forced marriages, an estimated 14.2 million people, are in Asia and the Pacific. This is followed by 14.5 per cent in Africa (3.2 million) and 10.4 per cent in Europe and Central Asia (2.3 million). When we account for the population in each region, prevalence of forced marriage is highest in the Arab States (4.8 per thousand population), followed by Asia and the Pacific (3.3 per thousand population).

• Over two-thirds of those forced to marry are female. This equates to an estimated 14.9 million women and girls. While women and girls account for the majority of people living in a forced marriage, men and boys are also subjected to forced marriage.

• Three in every five people in a forced marriage are in lower-middle income countries. However, wealthier nations are not immune, with 26 per cent of forced marriages in high or upper-middle income countries.

• Family members were responsible for the vast majority of forced marriages. Most persons who reported on the circumstances of forced marriage were forced to marry by their parents (73 per cent) or other relatives (16 per cent).

• The true incidence of forced marriage, particularly involving children aged 16 and younger, is likely far greater than current estimates can capture; these are based on a narrow definition and do not include all child marriages. Child marriages are considered to be forced because a child cannot legally give consent to marry.

Ending modern slavery

Through the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the global community has committed to ending modern slavery among children by 2025, and universally by 2030.

The report highlights some of the key policy priorities for addressing forced labour and forced marriage in the lead up to the 2030 target date for ending modern slavery.

Policy priorities for addressing forced labour

• Respect for the freedoms of workers to associate and to bargain collectively is indispensable to a world free from forced labour. These fundamental labour rights enable workers to exert a collective voice to defend their shared interests and to bargain collectively for secure and decent work, thus creating workplaces that are inimical to forced labour and workers who are resilient to its risks.

• Extend social protection, including floors, to all workers and their families, to mitigate the socio-economic vulnerability that underpins much of forced labour, and to provide workers with the basic income security to be able to say no to jobs that are abusive and to quit jobs that have become so.

• Promote fair and ethical recruitment, to protect workers from abusive and fraudulent practices during the recruitment and placement process, including the charging of extortionate fees and related costs by unscrupulous recruitment agencies and labour intermediaries. The global estimates indicate that a large share of forced labour cases can be traced to abuses occurring during the recruitment phase of their employment.

• Strengthen the reach and capacity of public labour inspectorates, so they are able to detect and act on labour violations before they deteriorate into forced labour.

• Ensure protection for people freed from forced labour, through immediate assistance, rehabilitation, and long-term sustainable solutions, so they can successfully recover and avoid re-victimisation.

• Ensure access to remedy for people freed from forced labour, to help recompense them for the consequences of their subjection to forced labour and to help in their recovery. Remedies include compensation for material damages (as medical costs, unpaid wages, legal fees, and loss of earnings and earning potential) or for moral damages (pain and emotional distress).

• Ensure adequate enforcement, to bring perpetrators to justice and deter would-be offenders from contemplating the crime of forced labour.

• Mitigate the heightened risk of forced labour and trafficking for forced labour in situations of crisis. Much of forced labour and human trafficking occurs in situations of crisis linked to armed conflicts, disasters, and disease. There is a need to mainstream prevention and protection measures across all phases of crisis responses, from pre-crisis preparedness to humanitarian action following crisis outbreak and on to post-crisis reconstruction and recovery.

• Combat forced labour and trafficking for forced labour in business operations and supply chains.

• End state-imposed forced labour, which accounts for one in seven of all forced labour cases.

Policy priorities for addressing forced marriage

• As women and girls are disproportionately affected, legislative and policy responses should have a gendered lens, including gender-sensitive laws, policies, programmes, and budgets, including gender-responsive social protection mechanisms. It is important that these initiatives are inclusive, equitable, and provide non-discriminatory access to migrants.

• Ensure adequate civil and criminal protections in national legislation. This should include raising the legal age of marriage to 18 without exceptions in order to protect children, criminalising the act of marrying someone who does not consent, regardless of age, and civil protections that protect the individual from marriage without having to penalise the perpetrators, who are often family members.

• Legislation is not in itself sufficient to end forced marriage and needs to be combined with wider preventative approaches addressing underlying discrimination and gender inequality, as well as related socio-cultural norms.

• Invest in building the agency of women and girls. Ensuring that women and girls have the opportunity and ability to complete school, earn a livelihood, and inherit assets plays a significant role in reducing vulnerability to forced marriage. To support this, institutions and employers should offer employment opportunities for women and girls.

• Protect the rights of those vulnerable to forced marriage and trafficking for forced marriage during times of crisis.

• Address the vulnerability of migrants, particularly children. This includes improving capacity to identify the most vulnerable, as well as ensuring equal access to safe, dignified return and sustainable reintegration such as social protection and services.

Manorama Yearbook app is now available on Google Play Store and iOS App Store