- World

- Mar 23

Forced labour generates $236 billion illegal profits per year

Illegal profits from forced labour worldwide have risen to $236 billion per year, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) said in a report based on 2021 global estimates.

The total amount of illegal profits from forced labour has risen by $64 billion (37 per cent) since 2014, a dramatic increase that has been fuelled by both a growth in the number of people forced into labour, as well as higher profits generated from the exploitation of victims.

What does the figure $236 billion indicate?

• This figure reflects the wages or earnings effectively stolen from the pockets of workers by the perpetrators of forced labour through their coercive practices.

• It represents money subtracted from the incomes of workers often already struggling to meet the needs of their families.

• For migrant workers, it is money taken from the remittances they send home to their families and relatives.

• For governments, these illegal profits represent lost tax revenue, because of the illicit nature of the gains and the jobs that generated them.

• More broadly, the profits from forced labour can incentivise further exploitation, strengthen criminal networks, encourage corruption and undermine the rule of law.

What is forced labour?

• ILO Forced Labour Convention, 1930, Article 2, states that forced or compulsory labour is “all work or service that is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which said person has not offered himself voluntarily”.

• Forced labour is defined, for purposes of measurement, as work that is both involuntary and under penalty or menace of a penalty (coercion).

• Involuntary work refers to any work undertaken without the free and informed consent of the worker.

• Coercion refers to the means used to compel someone to work without their free and informed consent.

Involuntary work and coercion can occur at any stage of the employment cycle:

a) At recruitment, to compel a person to take a job against their will.

b) During employment, to compel a worker to work and/or live under conditions to which they do not agree.

c) At the time of desired employment separation, to compel a person to remain in the job they wish to leave.

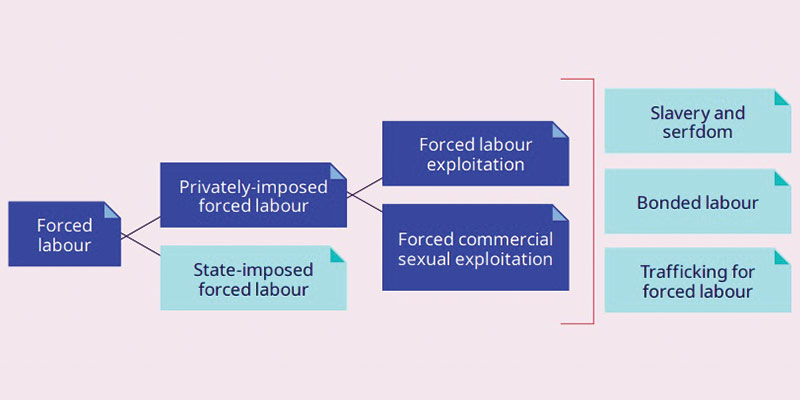

• For statistical purposes, forced labour can be divided into two broad categories — state-imposed forced labour and privately-imposed forced labour.

• State‐imposed forced labour refers to forms of forced labour that are imposed by state authorities, agents acting on behalf of state authorities, and organisations with authority similar to the state, regardless of the branch of economic activity in which it takes place.

• State-imposed forced labour accounts for 14 per cent of people in forced labour.

Privately-imposed forced labour

• Privately-imposed forced labour may take different forms including bonded labour and trafficking in persons for forced labour, as well as work exacted from victims of slavery and serfdom.

• Privately-imposed forced labour refers to forced labour in the private economy imposed by private individuals, groups, or companies in any branch of economic activity.

• It may include activities such as begging for a third party.

For the purpose of measurement, privately-imposed forced labour is commonly divided into two sub-types:

i) Forced labour exploitation (FLE): It refers to forced labour in the private economy imposed by private individuals, groups, or companies in any branch of economic activity with the exception of commercial sexual exploitation.

ii) Forced commercial sexual exploitation (FCSE): It refers to forced labour imposed by private agents for the purpose of commercial sexual exploitation.

Forced labour in the private economy

• Most forced labour occurs in the private economy.

• Nearly nine out of every 10 (86 per cent) instances of forced labour are imposed by private actors – 63 per cent in forced labour exploitation and 23 per cent in forced commercial sexual exploitation.

• Forced labour touches virtually all parts of the private economy. Among cases of forced labour in the private economy where the type of work was known, the four broad sectors accounting for the majority of total forced labour (89 per cent) are industry, services, agriculture, and domestic work.

These sectors are defined as follows:

i) The industry sector includes mining and quarrying, manufacturing, construction and utilities.

ii) The services sector encompasses activities related to wholesale and trade, accommodation and food service activities, art and entertainment, personal services, administrative and support services, education, health and social services, and transport and storage.

iii) The agriculture sector includes forestry, hunting as well as the cultivation of crops, livestock production and fishing.

iv) Domestic work is performed in third party households.

• Other sectors form smaller shares of total forced labour in the private economy but nonetheless still account for hundreds of thousands of people. These include people forced to beg on the street, and people forced into illicit activities.

Key points of the report:

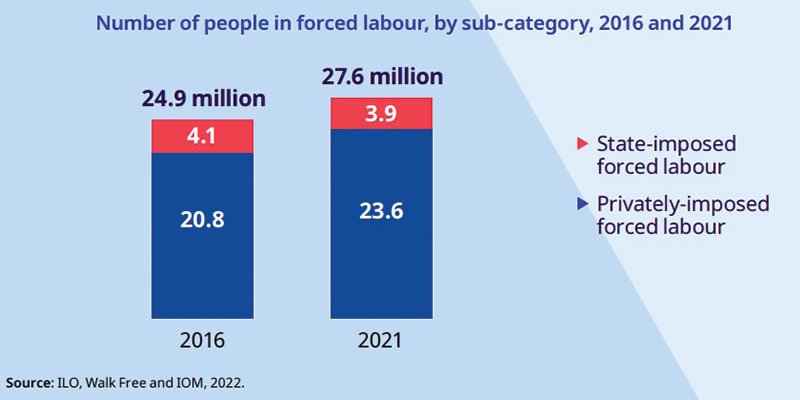

• There were 27.6 million people in forced labour on any given day in 2021. This figure translates to 3.5 people for every 1,000 people in the world. Between 2016 and 2021, the number of people in forced labour increased by 2.7 million, resulting in a rise in the prevalence of forced labour from 3.4 to 3.5 per 1,000 people. The overall rise was the product of an increase in the number of people in privately-imposed forced labour.

• Forced sex work generates more than two-thirds of profits, even though it only involves around one in four of the overall number of people forced to work illegally. This is because exploiters make more than $27,000 a year from each illegal sex worker, which is far more than the average $3,600 in profits generated by most other forms of forced labour. Of the $236 billion made from the use of forced labour, almost $173 billion was generated in forced commercial sexual exploitation.

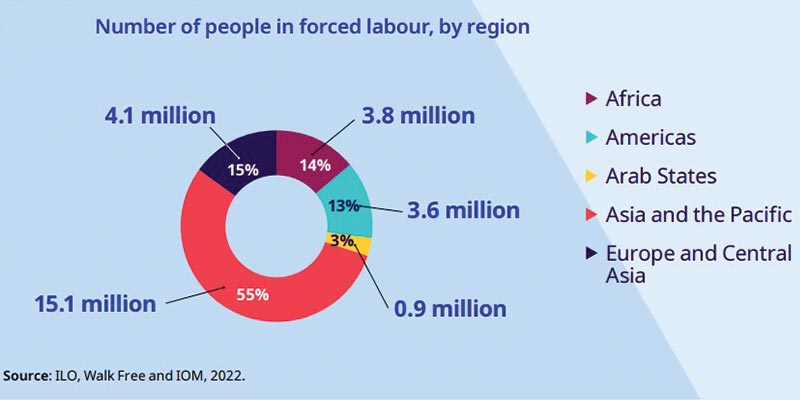

• No region of the world is spared from forced labour. Asia and the Pacific is host to more than half of the global total (15.1 million), followed by Europe and Central Asia (4.1 million), Africa (3.8 million), the Americas (3.6 million), and the Arab States (0.9 million).

• But this regional ranking changes considerably when forced labour is expressed in terms of prevalence (i.e., as a proportion of the population). By this measure, forced labour is highest in the Arab States (5.3 per thousand people), followed by Europe and Central Asia (4.4 per thousand), the Americas and Asia and the Pacific (both at 3.5 per thousand), and Africa (2.9 per thousand).

• An estimated 6.3 million people were in situations of forced commercial sexual exploitation on any given day in 2021. Gender is a key determining factor: nearly four out of every five (78 per cent) people trapped in these situations are girls or women. Children account for one in four (27 per cent) of the total cases.

How to tackle forced labour?

• Urgent investment is needed in enforcement measures that stem the profits from forced labour and bring perpetrators to justice.

• Currently, prosecutions for the crime of forced labour remain very low in most jurisdictions, meaning perpetrators are able to profit from their actions with impunity.

• Effective enforcement starts with strengthening the legal architecture around forced labour and bringing it into line with international legal standards.

• Ensuring adequate enforcement capacity is also critical, including through enhanced training programs to equip key enforcement actors with the skills and knowledge needed to effectively identify and prosecute forced labour cases.

• Extending the reach of labour inspectorates into high-risk sectors and building more effective bridges between labour and criminal law enforcement is also critical in this regard.

• Improving access to remedies so that perpetrators are obliged to pay compensation to those they have harmed can also serve a punitive function and act as a deterrent for would-be offenders.

• However, forced labour cannot be ended through law enforcement measures alone. Rather, a broad-based approach is needed, with a strong emphasis on addressing root causes and the protection of victims.

• Efforts in social protection, education, skills training and good migration governance are all critical in this regard. Promoting fair recruitment processes is also crucial, given that forced labour cases can often be traced back to recruitment abuses as well as the apparent importance of unlawful recruitment fees and costs as a source of illegal profit from forced labour.

• Ensuring the freedom of workers to associate and to bargain collectively is also essential to building resilience to the risks of forced labour.

• Formalising the informal economy, where forced labour risks are most pronounced, constitutes a key overarching priority across all these policy areas.

Manorama Yearbook app is now available on Google Play Store and iOS App Store