- World

- Dec 16

Over 30 people drown every hour globally

• The World Health Organisation (WHO) published its first-ever report on drowning prevention.

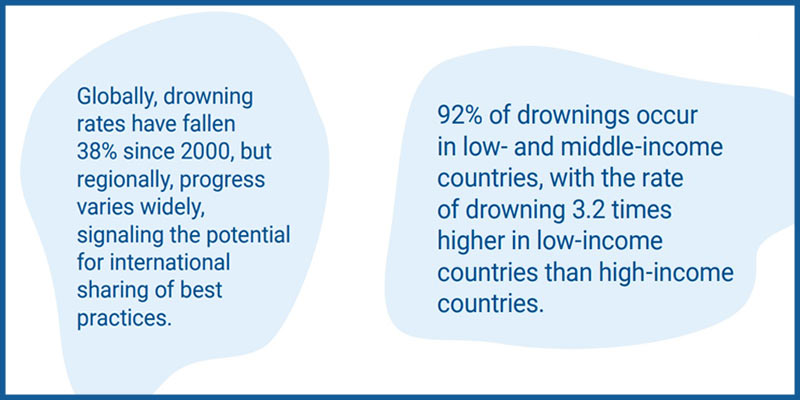

• It recorded a 38 per cent drop in the global drowning death rate since 2000 — a major global health achievement.

• However, the report notes that drowning remains a major public health issue with more than 30 people estimated to be drowning every hour and 300, 000 people dying by drowning in 2021 alone.

• Almost half of all drowning deaths occur among people below the age of 29 years, and a quarter occur among children under the age of 5 years.

• Children without adult supervision are at an especially high risk of drowning.

• Drowning is the process of experiencing respiratory impairment from submersion/immersion in liquid.

• Non-fatal drowning incidents lead to severe long-term neurological complications and disabilities that require prolonged care.

• The Indian government reported 36,362 drowning deaths in 2021.

Key points of the report:

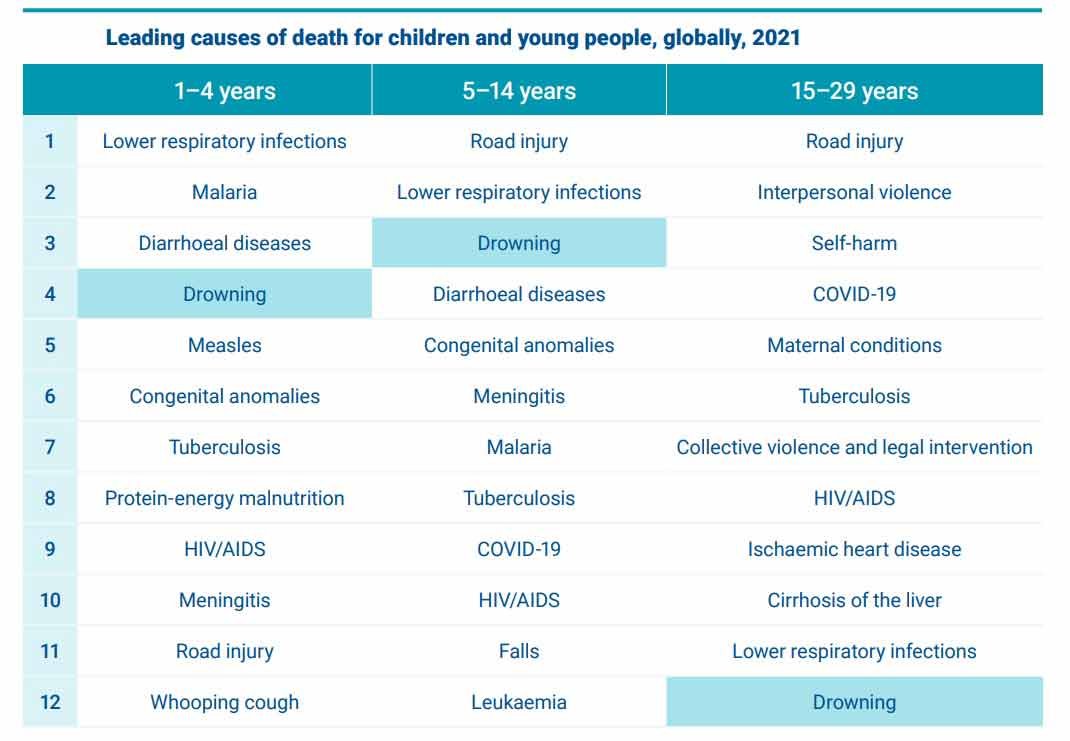

• Children aged under 5 years account for the largest single share of drowning deaths (24 per cent), with a further 19 per cent of deaths among children aged 5-14 years, and 14 per cent among young people aged 15-29 years.

• Globally, drowning is the fourth leading cause of death for children aged 1-4 years and the third leading cause of death for children aged 5-14 years.

• Drowning deaths remain a tragic and preventable public health crisis, and the declines seen in the past two decades fall short of what is needed to meet the wide range of SDG targets to which drowning prevention can contribute.

• The African Region and the South-East Asia Region have the greatest concentrations of countries with high drowning death rates.

• Progress in reducing drowning has been uneven. At the global level, nine in 10 drowning deaths take place in low and middle-income countries.

• The WHO European Region saw a 68 per cent drop in drowning death rate between 2000 and 2021, yet the rate fell by just 3 per cent in the WHO African Region, which has the highest rate of any region with 5.6 deaths per 100,000 people. This may be influenced by the levels of national commitments to address the issue.

• Within the African Region, only 15 per cent of countries had a national strategy or plan for drowning prevention, compared to 45 per cent of countries in the European Region.

• More than 7.2 million people, mainly children, could die by drowning by the year 2050 if current trends continue. Yet most drowning deaths could be prevented by implementing WHO-recommended interventions.

Key risk factors:

• Lack of supervision: Lack of barriers controlling exposure to water bodies and lack of adequate, close supervision for infants and young children are a drowning risk, as are poor swim skills and low awareness of water dangers.

• Age: Young children are at a particularly high risk of drowning due to an underdeveloped ability to assess risk, and a lack of swimming and water safety skills.

• Riskier behaviour: The drowning death rate among males is more than twice as high as females. Males are also more likely to be hospitalised than females for non-fatal drowning. Studies suggest that the higher drowning rates among males are due to increased exposure to water and riskier behaviour such as swimming alone, drinking alcohol before swimming alone and boating.

• Poverty: Drowning disproportionately affects poor and marginalised people. Whether it be through the use of ponds, rivers or lakes for bathing and washing clothing, or using open wells for collecting water, the pattern of daily exposure in low- and middle-income countries brings a higher risk of drowning.

• Occupational exposure: Individuals with occupations such as commercial or subsistence fishing face a substantially higher risk of drowning. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation estimates that more than 32,000 fishers die while working every year. Climate change has aggravated the hazardous conditions under which most fishers work, as extreme weather and natural disasters become more prevalent and destructive.

• Climate-related risks: Climate change is causing more extreme weather events, such as floods and heatwaves. Drowning accounts for 75 per cent of deaths in flood disasters. Drowning risks due to floods are particularly high in low and middle-income countries where early warning systems and flood mitigation infrastructure are underdeveloped.

• Transport on water: Travelling on water, particularly in dangerous weather conditions or without appropriate safety equipment, can increase drowning risk. Daily commuting often takes place on overcrowded and unsafe vessels, operated by staff who have not been trained to recognise hazardous conditions or perform high-seas navigation.

• Migration and seeking refuge: Increasing numbers of people are being displaced or migrating due to conflict, political and or economic instability and climate change. Many people resort to irregular channels for migration that are extremely hazardous, including across large expanses of water in treacherous conditions, often using overcrowded, unsafe vessels that lack safety equipment or are operated by untrained personnel.

Actions that can help prevent drowning:

i) Install barriers controlling access to water.

ii) Provide safe places away from water for pre-school children, with capable child care.

iii) Teach school-age children basic swimming, water safety and safe rescue skills.

iv) Train bystanders in safe rescue and resuscitation.

v) Strengthen public awareness of drowning and highlight the vulnerability of children.

vi) Set and enforce safe boating, shipping and ferry regulations.

vii) Build resilience and manage flood risks and other hazards locally and nationally.

viii) Coordinate drowning prevention efforts with those of other sectors and agendas.

ix) Develop a national water safety plan.

Legislation remains an underutilised tool for drowning prevention

• Legislation is an underused drowning-prevention tool. In some cases, legislation addressing specific drowning risks has high coverage, yet the comprehensiveness of individual laws varies greatly.

• For example, although 81 per cent of participating countries, covering six billion people, report some type of legislation for the safety of domestic passenger transport vessels, specific attributes to ensure passenger safety are often omitted in the legislation itself.

• Just 38 per cent of submitted laws list specific life-saving equipment required onboard passenger vessels. Only 17 per cent of laws state a ban on the boarding of crew or passengers in a state of intoxication. Just 12 per cent of laws require emergency plans for passenger vessels.

• In other cases, there is a notable absence of legislation to address specific drowning risks. Just 14 per cent of participating countries, covering 630 million people, report having national laws for fencing around the perimeter of private and/or public swimming pools for preventing unsupervised access by children.

Manorama Yearbook app is now available on Google Play Store and iOS App Store