- India

- Jan 21

- Chandra Bhushan

Australia on fire has plenty to teach us

A picture is worth a thousand words. This saying goes perfectly with the images coming from Australia. Deep orange hue enveloping the sky, fire tornados, terrified people being evacuated from beaches, a charred joey (baby kangaroo) hanging on a fence wire, a scorched koala and cities engulfed in thick smoke. These poignant images illustrate the devastation that forest fires have caused across Australia since September.

While the mainstream media is calling them ‘bushfires’, the current fires are distinctly different and fall under the category of ‘megafires’. Megafires, typically defined as those covering more than 40,000 hectares, are accelerated by high temperatures and drought. They are extremely challenging to contain and are usually contained when all the available burnable vegetation is exhausted.

But what has happened, and continues to happen, in Australia should be called ‘super megafires’. I say this because the scale of the devastation that forest fires have inflicted upon Australia is unheard of. About 11.5 million hectares of forests have gone up in smoke so far. This is an area bigger than the whole of Punjab and Haryana put together. Though the loss of life and property is relatively low - about 30 people are dead, and 2,500 homes have been destroyed or damaged - the destruction of wildlife has been colossal.

More than 1 billion animals - mammals, birds and reptiles - have lost their lives in the inferno. But even these huge losses of individual animals and plants do not reveal the full scale of impact that the recent fires have had on biodiversity.

Reports by Australian researchers indicate that 99 per cent of the area burned in the current fires contains potential habitat for at least one nationally listed threatened species. An estimated 6 million hectares of threatened species habitat has been burned. Approximately 70 nationally threatened species have had at least 50 per cent of their range burnt, while nearly 160 threatened species have had more than 20 per cent of their range burnt. What implications the loss of habitat will have on the future of many of the species, only time will tell.

Air pollution has become another disaster. On January 1, Australia’s capital Canberra recorded the worst pollution it has ever seen, with the air quality index 23 times higher than “hazardous level”. As I write this, Melbourne is still blanketed by hazardous smoke. The smoke has reached New Zealand, 1,600 km away, and has drifted across the South Pacific Ocean, reaching Buenos Aires in Argentina.

The fact is the continent has been burning continuously for the past five months, and Australians have not been able to defeat the blaze even with all their resources and technological might. They are now praying for the rain gods to come to their rescue.

Forest fires are part of Australia’s ecology. Eucalyptus forests in Australia have a unique relationship to fire; the trees actually depend on fire to release their seeds. Every year, some or other part of forests catch fire and are quelled naturally or by firefighters.

However, this year’s fires are unprecedented. It started much earlier and got very big, very quickly and has continued uninterrupted till now. The weather conditions feeding the fires are also historic. Last year was the continent’s hottest and driest on record. The annual mean temperature was 1.5 degrees Celsius above the long-run average - the highest since records began in 1910. Meanwhile, the amount of rainfall was 40 per cent below the long-term average, the lowest since 1900. The extreme heat and drought created more tinder to fuel fires.

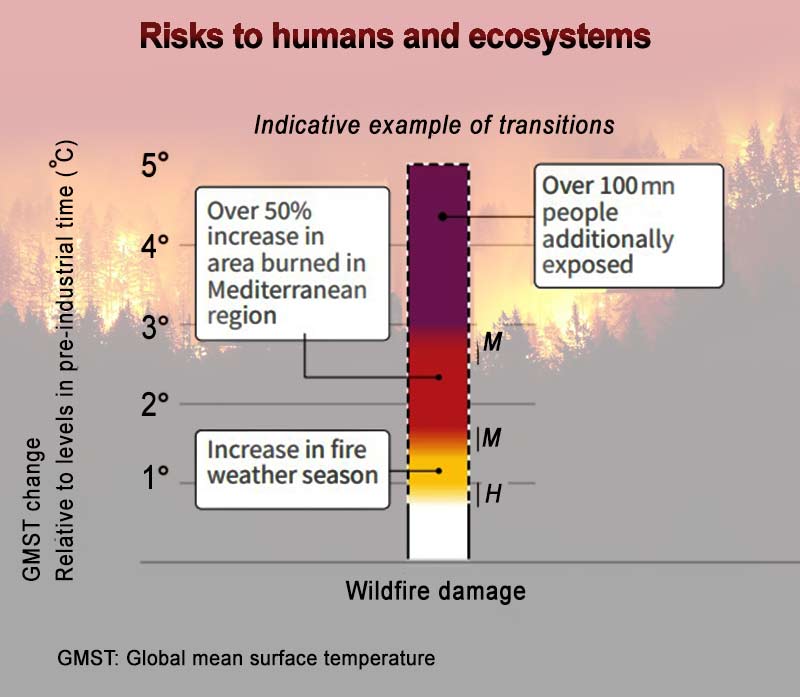

There is a definite tell-tale sign of climate change in Australia’s forest fires. Higher temperatures, extreme dryness, lengthening fire seasons and the rapid spread of forest fires fall precisely in the scenarios that the climate models have predicted for decades. But these predictions are not only for Australia; they hold true for a large number of countries, including India.

Many regions of the world share similar conditions that have set Australia ablaze. The west coast of the US, the Mediterranean, South Africa, parts of Central Asia and parts of South and Central India have predispositions for similar firestorms. These parts of the world are already experiencing increasing forest fires.

In 2018, California had its deadliest forest fires in history and more than 100 people died in wildfires in Greece. India too has experienced some of its worst forest fires in 2018 and 2019. In fact, the forest fire incidents in India has more than doubled since 2015 - from 15,937 incidents in 2015 to 29,547 in 2019. There is a clear signal of increasing forest fires in central and southern states.

Maybe India is not likely to see such large-scale contiguous forest fires like Australia, as we have fragmented our forests significantly. Still, intense forest fires like we saw in Tehri and Bandipur in 2019 could become widespread.

So, what do we do to avoid the tragedy that has befallen Australia? The first and foremost thing to do is to learn lessons, and there are many important ones to learn.

The first is that the climate crisis is not something that will happen in the future; it is happening now, in front of our eyes. We are witnessing the worst impacts of climate change at a much lower temperature increase than has been predicted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. So, let’s prepare for the worst scenario.

Two, as the world gets warmer and drier, and forest fires become more frequent and severe, we will have to learn to live with forest fires. The means we will have to zone our forests based on their propensity to fire and design management systems accordingly. For instance, about one-third of India’s forests is fire-prone. We should quickly assess these areas carefully for fire management systems and assess the risks to habitation and infrastructure.

Three, the older ways of containing forest fires will become obsolete. Australia’s forest fire management rules are considered the best in the world, yet they failed to control the fires. For example, in Australia, the fire lines or fire breaks didn’t work because the fire type was ‘crown fire’. Crown fire burns the top of trees and spread rapidly by the wind. So, we need to develop new methods for firefighting.

Four, our forestry practices will have to change drastically. For instance, we have been promoting eucalyptus plantations across the country. We will have to seriously look into this practice as eucalyptus plantations have been singled out for crown fire. Similarly, how to deal with invasive alien species like Lantana has become more critical than ever. In some parts of Australia, Lantana is being linked with the severity of the forest fires.

Lastly, the firestorm in Australia is a clear reminder of our inability to deal with large-scale extreme events. Even with all our technological might, we will not be able to save lives, properties and ecosystems. Therefore, it is essential that we do everything possible to contain global warming within 1.5 degrees Celsius. This is the only chance to avoid large-scale death and destruction.

Chandra Bhushan is an environmentalist and a researcher, writer and campaigner for sustainable development. He was honoured with the Ozone Award by UN Environment in 2017 for his contributions to climate change mitigation and ozone layer protection. The views expressed here are personal.

Manorama Yearbook app is now available on Google Play Store and iOS App Store