- India

- Oct 16

India slips to 101 in Global Hunger Index

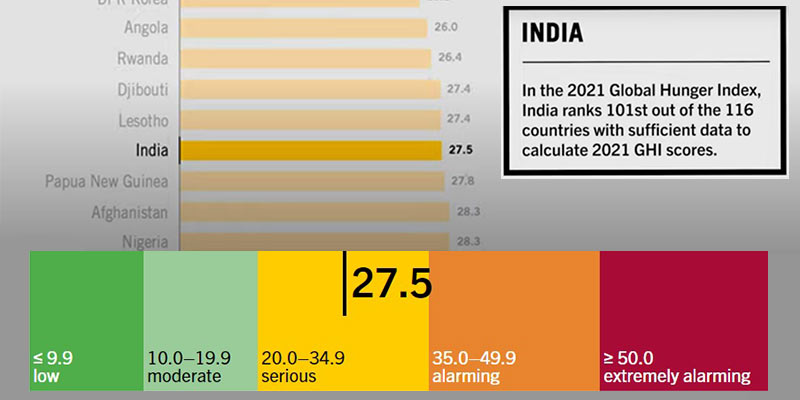

India has slipped to 101st position in the Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2021 of 116 countries, from its position of 94th in 2020.

The report, prepared jointly by Irish aid agency Concern Worldwide and German organisation Welthungerhilfe, termed the level of hunger in India “serious”.

In 2020, India was ranked 94th out of 107 countries. Now with 116 countries in the fray, it has dropped to 101st rank.

The share of wasting among children in India rose from 17.1 per cent between 1998-2002 to 17.3 per cent between 2016-2020.

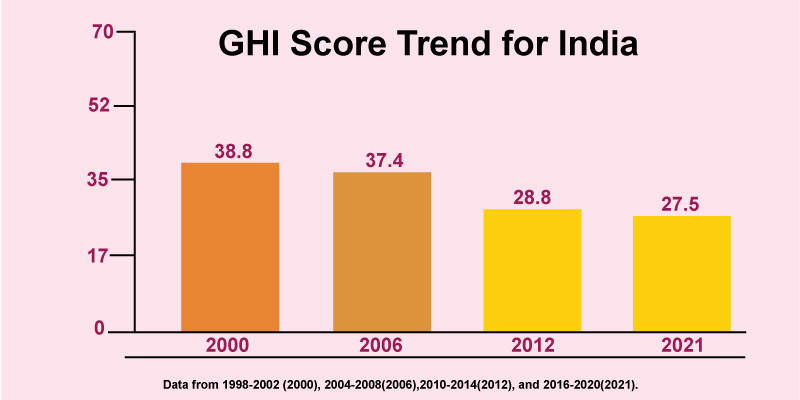

However, India has shown improvement in other indicators such as the under-5 mortality rate, prevalence of stunting among children and prevalence of undernourishment owing to inadequate food.

The ministry of women and child development said it was shocking that India’s rank was lowered on the Global Hunger Index and it termed the methodology used for rankings “unscientific”.

Neighbouring countries like Nepal (76), Bangladesh (76), Myanmar (71) and Pakistan (92) have fared better in the index.

What is the Global Hunger Index?

The Global Hunger Index (GHI) is a tool designed to comprehensively measure and track hunger at global, regional, and national levels. It is a peer-reviewed annual report, jointly published by Concern Worldwide and Welthungerhilfe.

GHI scores are calculated each year to assess progress and setbacks in combating hunger. It is designed to raise awareness and understanding of the struggle against hunger, provide a way to compare levels of hunger between countries and regions, and call attention to those areas of the world where hunger levels are highest and where the need for additional efforts to eliminate hunger is greatest.

How are the scores calculated?

GHI scores are calculated using a three-step process that draws on available data from various sources to capture the multidimensional nature of hunger.

First, for each country, values are determined for four indicators:

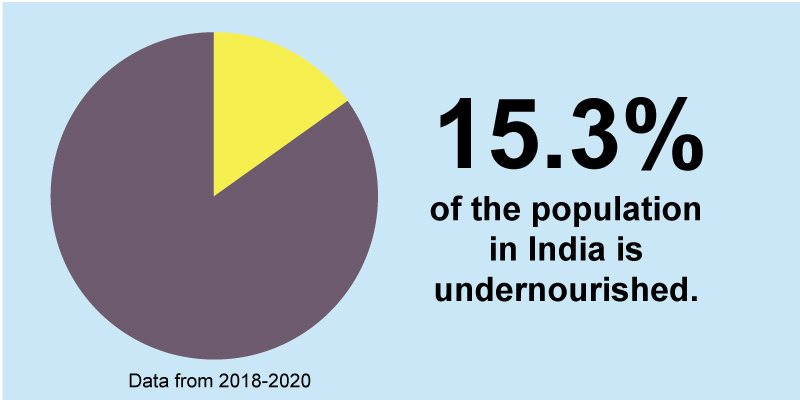

• Undernourishment: The share of the population that is undernourished (that is, whose caloric intake is insufficient).

• Child Wasting: The share of children under the age of five who are wasted (that is, who have low weight for their height, reflecting acute undernutrition).

• Child Stunting: The share of children under the age of five who are stunted (that is, who have low height for their age, reflecting chronic undernutrition).

• Child Mortality: The mortality rate of children under the age of five (in part, a reflection of the fatal mix of inadequate nutrition and unhealthy environments).

Second, each of the four component indicators is given a standardised score on a 100-point scale based on the highest observed level for the indicator on a global scale in recent decades.

Third, standardised scores are aggregated to calculate the GHI score for each country, with each of the three dimensions (inadequate food supply, child mortality and child undernutrition, which is composed equally of child stunting and child wasting) given equal weight.

This three-step process results in GHI scores on a 100-point GHI Severity Scale, where 0 is the best score (no hunger) and 100 is the worst.

Key points of 2021 Global Hunger Index:

• As many as 18 countries, with a GHI score of less than 5, are collectively ranked at the top of the index. These are Belarus, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Brazil, Chile, China, Croatia, Cuba, Estonia, Kuwait, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Turkey and Uruguay.

• The 2021 Global Hunger Index (GHI) points to a dire hunger situation in a world coping with multiple crises. Conflict, climate change, and the COVID-19 pandemic — three of the most powerful and toxic forces driving hunger—threaten to wipe out any progress that has been made against hunger in recent years.

• Progress toward Zero Hunger by 2030, already far too slow, is showing signs of stagnating or even being reversed. Based on current GHI projections, the world as a whole—and 47 countries in particular—will fail to achieve a low level of hunger by 2030.

• The consequences of climate change are becoming ever more apparent and costly, but the world has developed no fully effective mechanism to mitigate, much less reverse, it.

• Although GHI scores show that global hunger has been on the decline since 2000, progress is slowing.

• After decades of decline, the global prevalence of undernourishment — one of the four indicators used to calculate GHI scores — is increasing. This shift may be a harbinger of reversals in other measures of hunger.

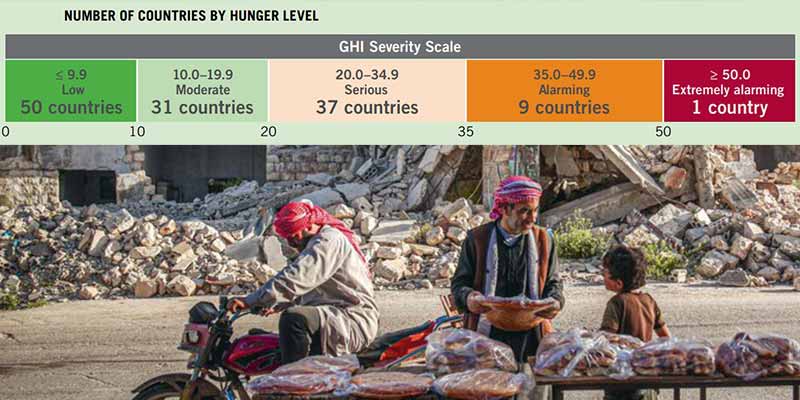

• According to the 2021 GHI, one country, Somalia, suffers from an extremely alarming level of hunger. Hunger is at alarming levels in 5 countries — Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Madagascar, and Yemen. It is provisionally categorised as alarming in four additional countries — Burundi, Comoros, South Sudan, and Syria.

• Hunger has been identified as serious in 31 countries and is provisionally categorised as serious in 6 additional countries.

• Africa South of the Sahara has the highest rates of undernourishment, child

stunting, and child mortality of any region of the world.

• In the regions of Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, East and Southeast Asia, and West Asia and North Africa, hunger levels are low or moderate.

Violent conflict drives hunger

The two-way links between hunger and conflict are well established. Violent conflict is destructive to virtually every aspect of a food system, from production, harvesting, processing, and transport to input supply, financing, marketing, and consumption. At the same time, heightened food insecurity can contribute to violent conflict. Without resolving food insecurity, it is difficult to build sustainable peace, and without peace the likelihood of ending global hunger is minimal.

More than half of the people facing undernourishment live in countries affected by conflict, violence, or fragility. Of the 155 million people in a situation of acute food crisis, emergency, or catastrophe in 2020, conflict was the primary driver of hunger for 99.1 million people in 23 countries.

Conflict is a consistent predictor of child malnutrition, particularly as measured by child stunting. Conflict also increases child mortality directly through injuries and trauma and indirectly through diarrhea, measles, malaria, lower respiratory tract infections, and malnutrition associated with poor living conditions and damaged health care infrastructure.

Some important definitions

What is hunger?

The problem of hunger is complex, and different terms are used to describe its various forms.

Hunger is usually understood to refer to the distress associated with a lack of sufficient calories. The Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) defines food deprivation, or undernourishment, as the consumption of too few calories to provide the minimum amount of dietary energy that each individual requires to live a healthy and productive life, given that person’s sex, age, stature, and physical activity level.

What is Undernutrition?

Undernutrition goes beyond calories and signifies deficiencies in any or all of the following: energy, protein, and/ or essential vitamins and minerals. Undernutrition is the result of inadequate intake of food in terms of either quantity or quality, poor utilization of nutrients due to infections or other illnesses, or a combination of these factors. These, in turn, are caused by a range of factors, including household food insecurity; inadequate maternal health or childcare practices; or inadequate access to health services, safe water, and sanitation.

What is Malnutrition?

Malnutrition refers more broadly to both undernutrition (problems caused by deficiencies) and overnutrition (problems caused by unbalanced diets, such as consuming too many calories in relation to requirements with or without low intake of micronutrient-rich foods).

Manorama Yearbook app is now available on Google Play Store and iOS App Store