- World

- Jun 11

Major barriers to reproductive freedom

• The UN Population Fund (UNFPA) unveiled its flagship State of World Population report, warning that a rising number of people are being denied the freedom to start families due to skyrocketing living costs, persistent gender inequality, and deepening uncertainty about the future.

• Titled ‘The real fertility crisis: The pursuit of reproductive agency in a changing world’, the report argues that what Is really under threat is people’s ability to choose freely when and whether to have children.

• The report draws on a recent UNFPA/YouGov survey covering 14 countries that together represent 37 per cent of the global population.

Gradual shift as a result of progress

• The last century saw major advances in healthcare and development, propelling the largest population expansion in human history – one broadly viewed as a “population bomb” when it came to people in the Global South.

• A variety of anxieties took hold, ranging from concerns that overpopulation would stymie development and increase poverty, to the assumption that famine and mass death were unavoidable.

• Many leaders and advisers, especially those in developed countries, predicted a “race to oblivion” unless measures were implemented to control women’s fertility too often through practices such as coerced use of contraception and forced sterilisation or abortion.

• The number of people sharing our planet has more than tripled since 1950, while over that same period, the average fertility rate per woman has declined from 5 in 1950 to 2.25. It is expected to reach 2.1 by 2050.

• Unlike the vertiginous population declines that take place during wars or epidemics, these shifts have been gradual and in many ways deliberate, a result of progress in both life-extending and contraceptive medicine, among other advances.

Why people are not having the family sizes they desire?

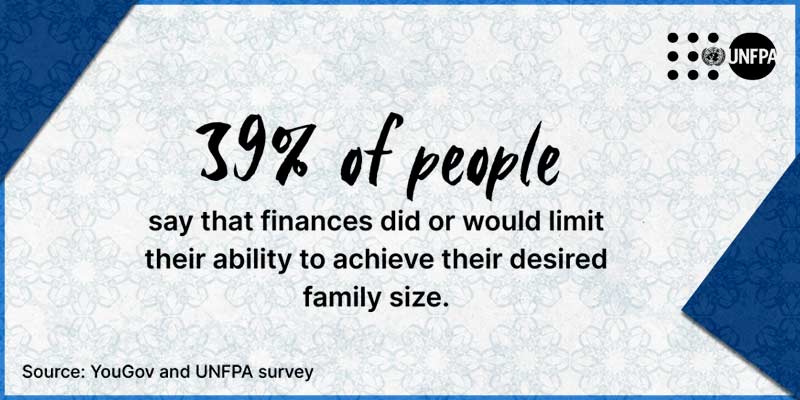

• Out of 10,000 people who reported having or wanting to have children, 39 per cent reported that financial limitations were a factor that had affected or would affect their ability to realise their desired family size.

• The second most commonly reported factor, at 21 per cent, was unemployment or job insecurity.

• The third, at 19 per cent, was housing concerns, such as lack of space or high cost. Notably, housing concerns are not linked solely to youth. They can be a barrier to people of all ages.

• Health barriers like poor general wellbeing, infertility, and limited access to pregnancy-related care add further strain.

• Many are also holding back due to growing anxiety about the future — from climate change to political and social instability.

• Partnership issues also played a clear role — 14 per cent of respondents said that the lack of a partner, or a suitable partner, had led or would lead to them having fewer children than desired. More than 10 per cent said their partner’s insufficient involvement in housework or childcare had led or would lead to this outcome.

• Beyond traditional barriers, emerging social realities are reshaping reproductive decisions.

• The report identifies a complex web of modern challenges: the growing “loneliness epidemic”, shifting relationship patterns, difficulties in finding supportive partners, social stigma around reproductive decisions, and deeply entrenched gender norms.

• Rising expectations around intensive parenting place disproportionate pressure on women, reinforcing unequal caregiving burdens and influencing decisions about if and when to have children.

Beyond baby bonuses: Recommended actions

• The report warns against simplistic and coercive responses to falling birth rates, such as baby bonuses or fertility targets, which are often ineffective and risk violating human rights.

• Recommended actions include making parenthood more affordable through investments in housing, decent work, paid parental leave and access to comprehensive reproductive health services.

• For decades, Eastern European countries have experimented with financial incentives – cash bonuses for new babies, tax breaks for larger families, even medals for mothers of multiple children.

• Increasingly, governments are becoming aware that economic incentives and awards are not meeting the full needs of parents.

• Cultural barriers to parenthood are persistent in many parts of the region, where women still bear the brunt of unpaid caregiving, and men are less likely to take parental leave.

• Regular cash transfers show somewhat more impact. For example, regular cash transfers had a small but noticeable impact on period total fertility in studies in Argentina, Hungary, Israel and Spain. Another example is from Poland, which in 2016 began providing substantial direct cash transfers to families with two or more children – amounting to 2 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product.

• The overarching indication is that longer-term financial security — whether through improved earning potential, greater job security or better economic conditions overall — is important for enabling people to realise their fertility goals.

• While short-term, limited or one-time financial transfers may help with child-related expenses, they may also just encourage parents to bring forward their childbearing plans in anticipation of the assistance disappearing. These parents might still ultimately forgo their desires for additional children.

India’s population touches 1.46 billion, fertility drops

• India’s population is estimated to reach 1.46 billion in 2025, continuing to be the highest in the world, according to the report.

• India’s total fertility rate has declined to 1.9 births per woman, falling below the replacement level of 2.1.

• This means that, on average, Indian women are having fewer children than needed to maintain the population size from one generation to the next, without migration.

• In 1960, when India’s population was about 43.6 crore, the average woman had nearly six children.

• Back then, women had less control over their bodies and lives than they do today. Fewer than one in 4 used some form of contraception, and fewer than one in two attended primary school, the report said.

• But in the coming decades, educational attainment increased, access to reproductive healthcare improved, and more women gained a voice in the decisions that affected their lives. The average woman in India now has about two children.

• States such as Bihar, Jharkhand, and Uttar Pradesh continue to experience high fertility rates, while others, like Delhi, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu, have sustained below-replacement fertility.

• This duality reflects differences in economic opportunities, access to healthcare, education levels, and prevailing gender and social norms.

What is the purpose of UNFPA?

• UNFPA is formally named the United Nations Population Fund. The organisation was created in 1969, the same year the United Nations General Assembly declared “parents have the exclusive right to determine freely and responsibly the number and spacing of their children”.

• Guided by the 1994 Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD), UNFPA partners with governments, civil society and other agencies to advance its mission.

• UNFPA works in more than 150 countries and territories.

• It is entirely supported by voluntary contributions of donor governments, inter-governmental organisations, the private sector and foundations and individuals, not by the United Nations regular budget.

• UNFPA, a subsidiary organ of the UN General Assembly, reports to the UNDP/UNFPA Executive Board of 36 UN Member States and receives overall policy guidance from the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC).

• UNFPA is the United Nations’ sexual and reproductive health agency. Its mission is to deliver a world where every pregnancy is wanted, every childbirth is safe and every young person’s potential is fulfilled.

Manorama Yearbook app is now available on Google Play Store and iOS App Store